ELSA ROUY : A DEMON IN A SUNDRESS

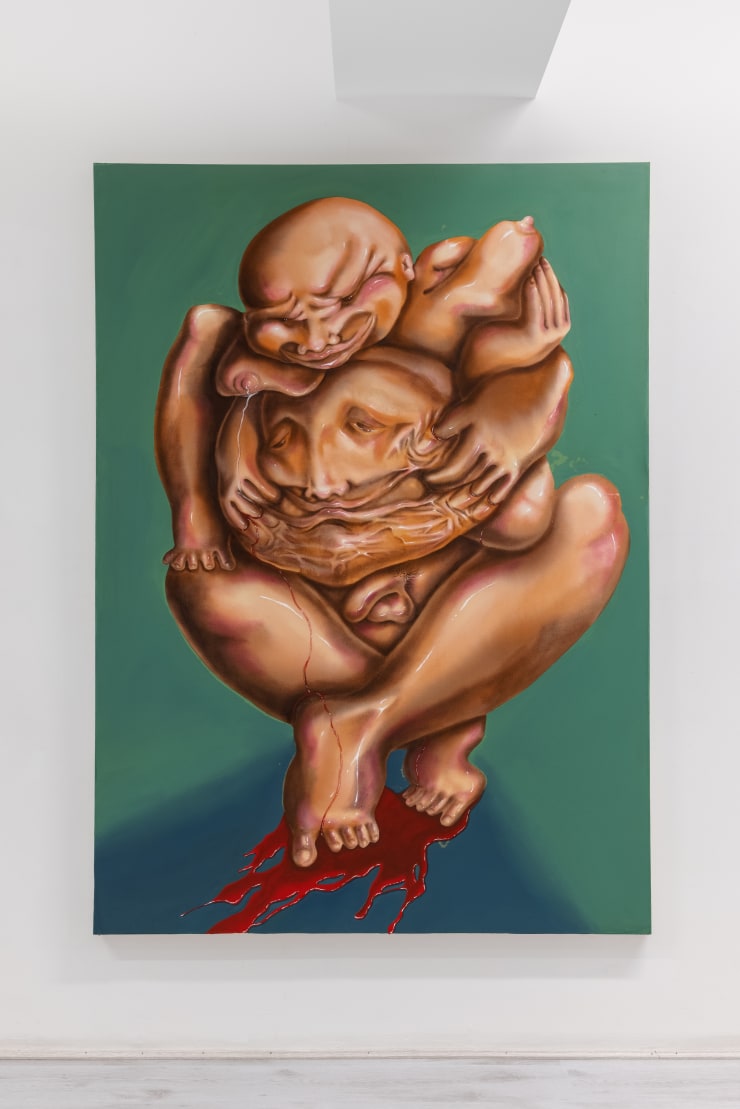

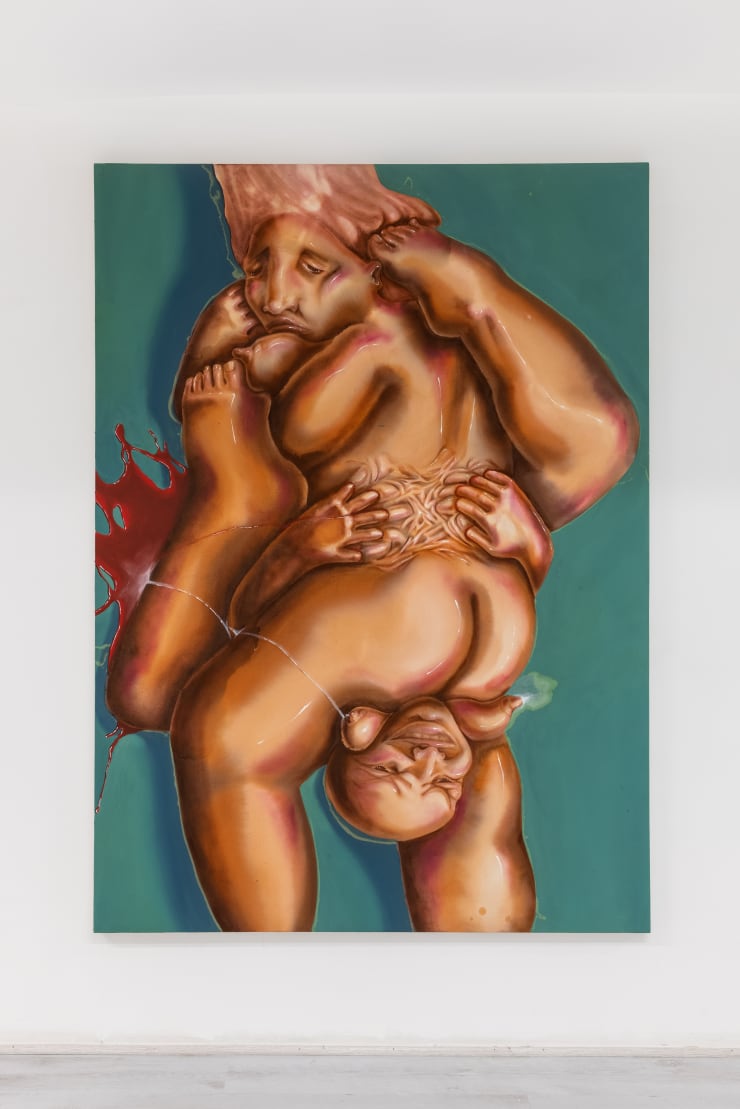

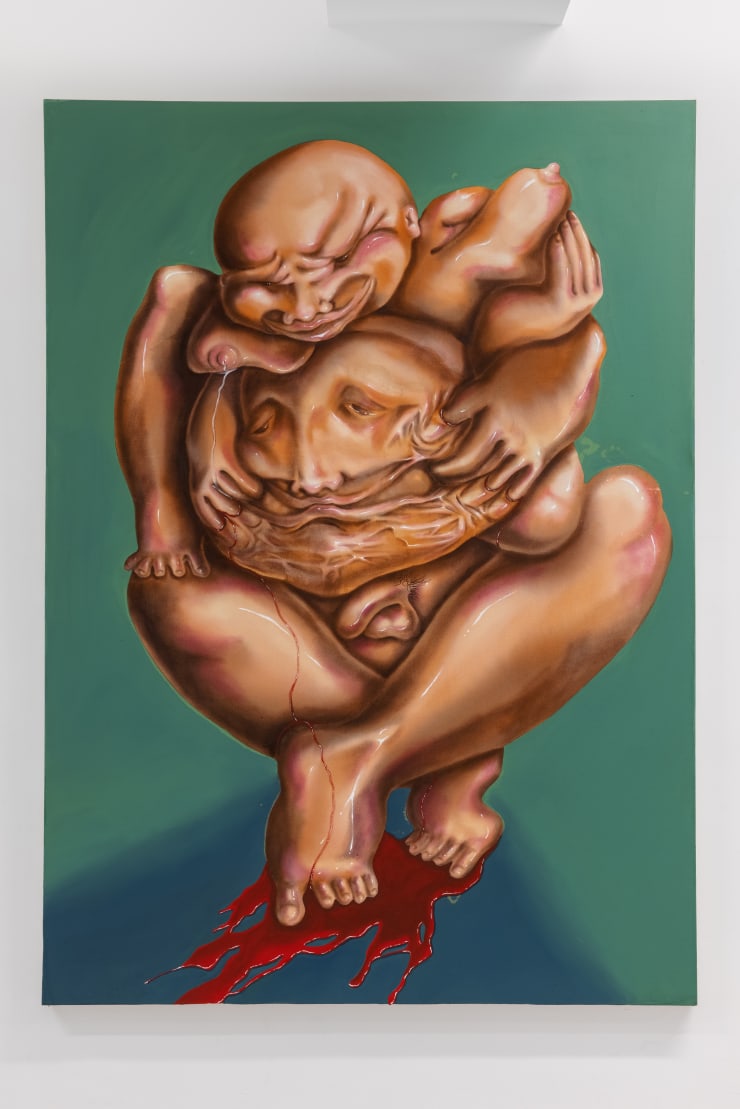

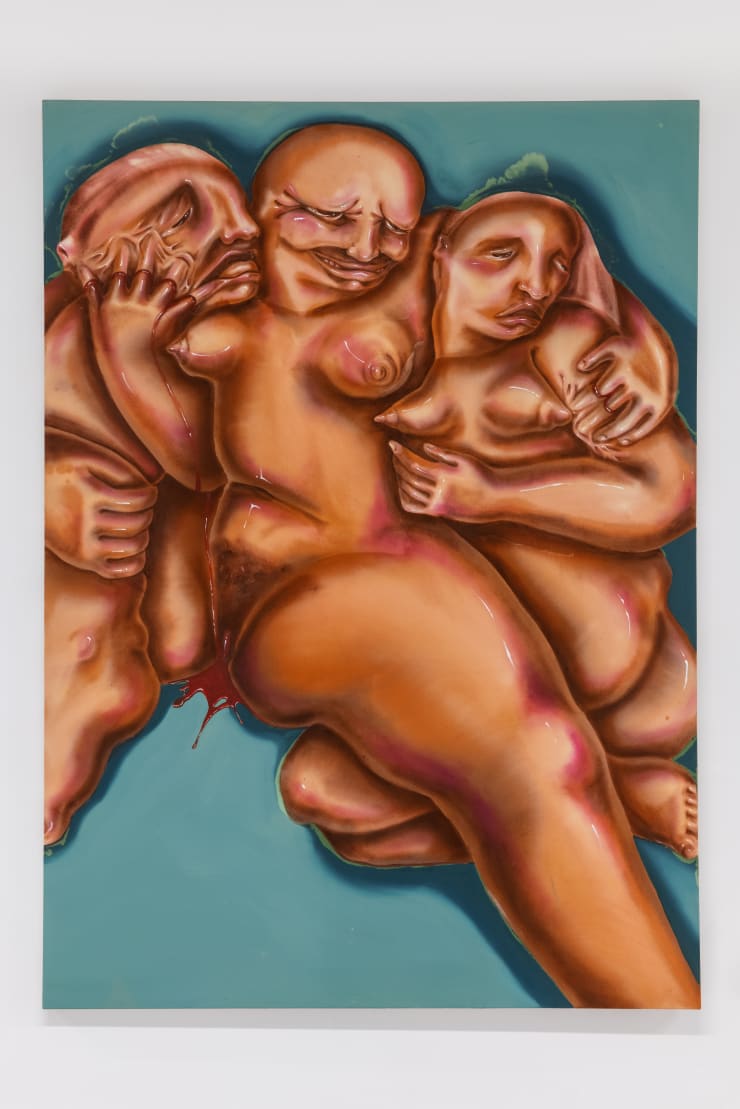

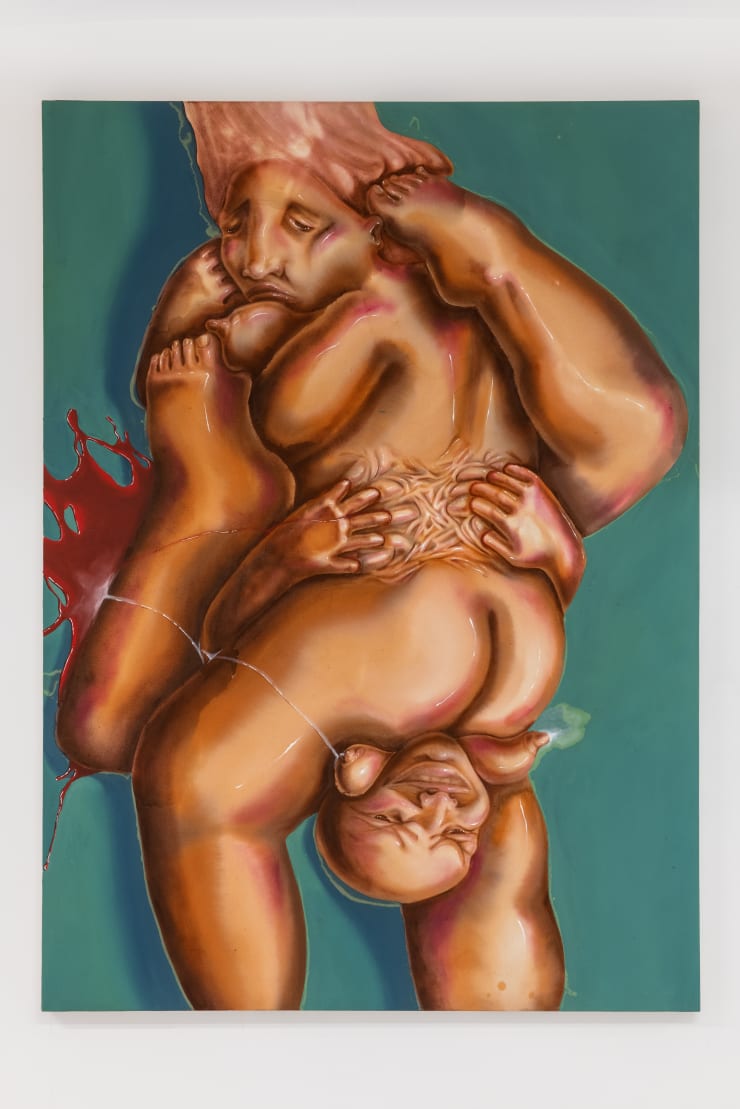

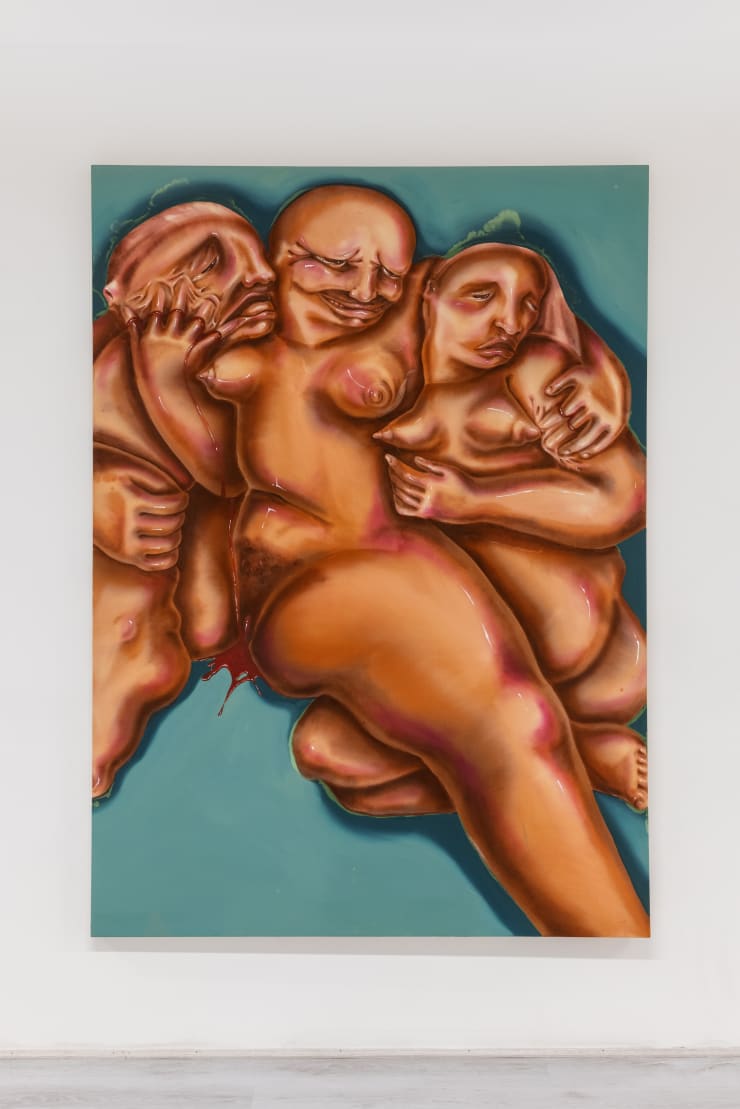

A Demon in a Sundress shows multiple bodies that are perverted, protruded, pushed andbreached through the timeline of a day. The figures are overpowered and ripped by Rouy’s enduring protagonist, who in the final scene overpowers herself, threatening to corrupt her existence.

Private View: 19th August 6-9pm

Location: 147 Stoke Newington High Street, London, N16 0NY

General Opening Hours: 11 - 6pm

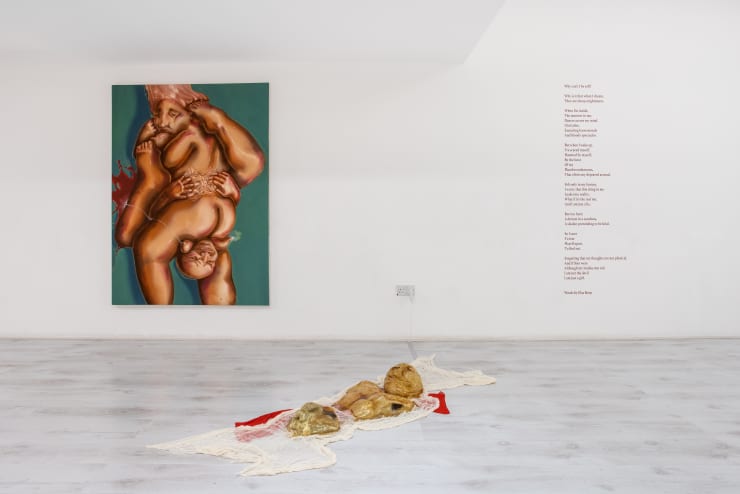

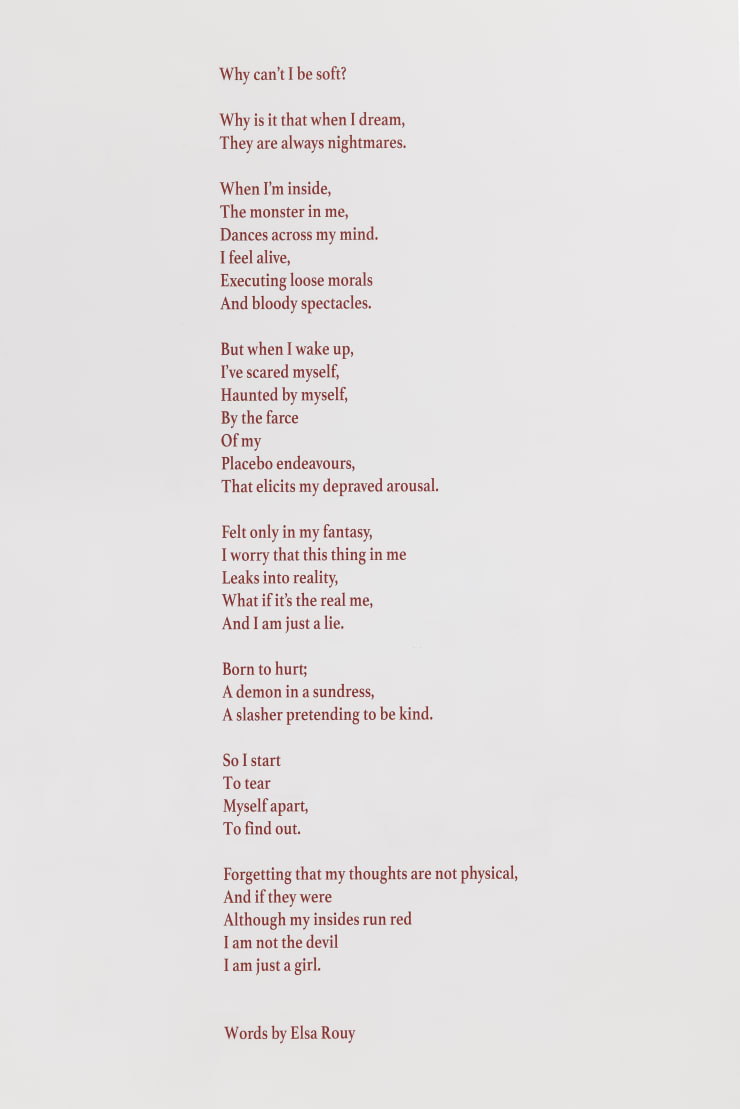

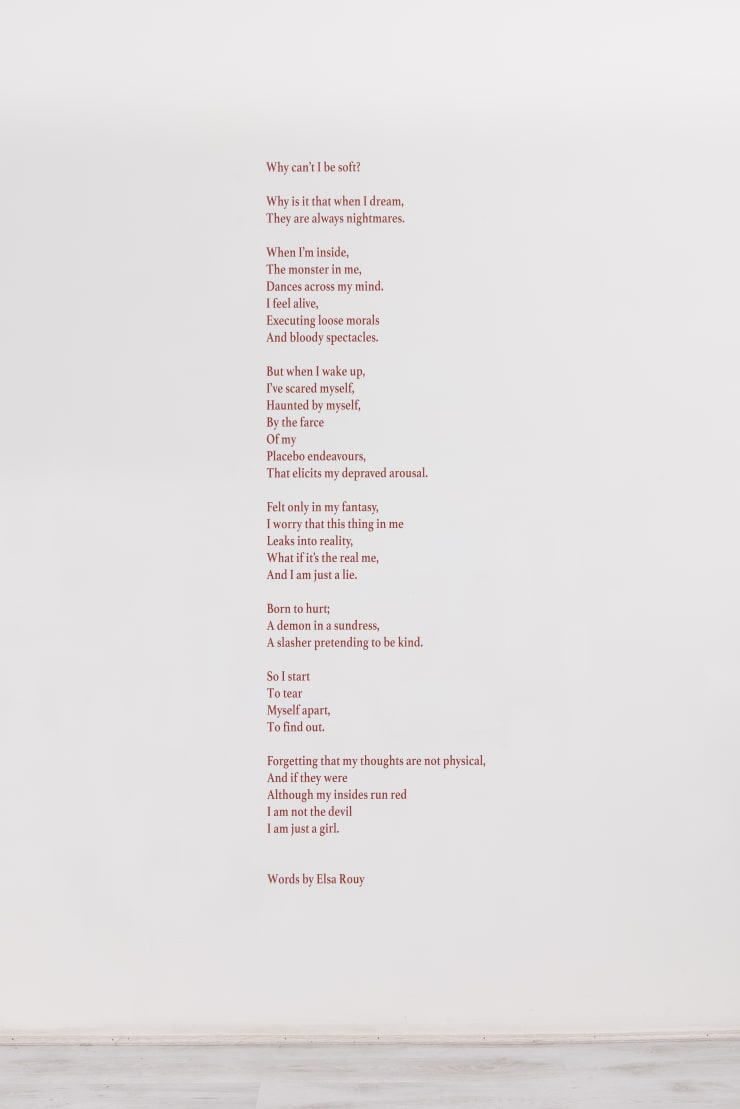

A Demon in a Sundress is Elsa Rouy’s (b. 2000, Kent) second solo show with Guts Gallery. Five paintings and two sculptures are displayed, accompanied by an original poem by Rouy. Influenced by personal experiences, these works are a culmination and evolution of themes explored throughout her practice. Rouy activates the space to form a disturbing and displaced narrative echoing longing, child-like dependency and a parasitic undertaking of relationships.

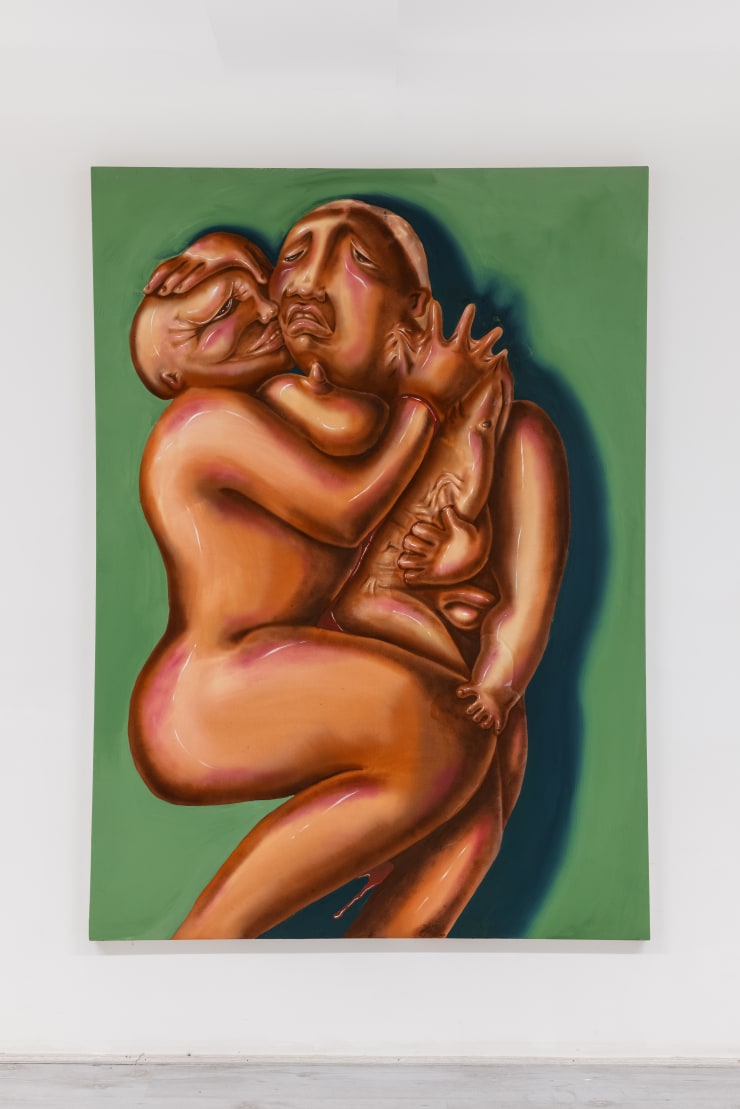

A Demon in a Sundress shows multiple bodies that are perverted, protruded, pushed and breached through the timeline of a day. The figures are overpowered and ripped by Rouy’s enduring protagonist, who in the final scene overpowers herself, threatening to corrupt her existence. The artworks are a pictorial embodiment of the ‘monstrous’, feared and unspoken part of Rouy. A part that feels ultimately accosting and taboo but familiar for the majority. The result is a series of mise en scenes filled with an ambiguity of space and personhood. An intrusive, dream-like state is formed that holds the figures in a catastrophic and violent snapshot filled with tension caused by the apprehension of the disastrous moment to come. A tension that is imitated in the puncturing of the amalgamation of bodies flicked with a white, sebaceous shine. Contorted and subdued, the bodies become a mass of engorged skin seemingly bursting with and leaking bodily fluids. Finalised by the latex sculptures - the aftermath revealed – resemble displaced and collapsed ghostly shells that resemble folds of skin. Each sculpture is embedded with the artist and friends’ hair and emits a small clouded diffuse of Ylang Ylang, Geranium, Neroli and Jasmine. An after thought that perhaps the main figure was soft all along.

About Elsa Rouy

London based artist Elsa Rouy (Sittingbourne, Kent) creates art with a female gaze. Rouy explores new ways of expressing semi-autobiographical and social narratives following a discourse related to the human condition.

She has an interest in female sexual expression and the imperfect-self. Her artworks satirize immoral thoughts that are terrifying, centring around feelings of shame and guilt. To explore this, Rouy paints hedonistic grotesque figures often of monstrous women with their sexual organs revealed. To imitate her hyperawareness of having a body she subverts and delocalizes depictions of female and male genitalia to form androgenous or fluid figures that resonate to the artist’s identity while also removing a fixed identity.

Rouy’s practice underlines the parts of ourselves that we find uncomfortable, accentuated by ardent depictions of bodily fluids; such as blood, pus, semen, faeces, milk, urine, sweat and saliva. There is a link between bodily fluids and the notion of being a human and our mortality. The leaking of bodily fluids breaks the containment associated with correctness and purity, which are constantly strived for in our society, our bodies and our minds. The bodily fluids are presented to expose the unsavoury parts of being human that are considered taboo.

Her artwork explores societal and internal power roles. Rouy appropriates the human body to discuss relationships between people and the self that are saturated with child-like dependency, intrusion and boundaries. Alongside a distortion of interior and exterior bodies, the artworks denote emotional illusion, trust and trepidation between people. The figures often have connections to expulsion and birth that act simultaneously as a harbouring or a needed release of these emotional burdens.

Instagram reviews of Elsa Rouy's artwork

"Disgusting and bad art"

☆☆☆☆☆

"Flesh and fuckery"

☆☆☆☆☆

"Damn I fricking LUV this. So weird and magnetising"

☆☆☆☆☆

“Fuck. ????❤️???? the picture was one thing but the title literally took my breath away”

☆☆☆☆☆

“Wild painting”

☆☆☆☆☆

Playlist curated by the artist

On the edge of non-existence and hallucination; of a reality that — if I acknowledge it — annihilates me.

Julia Kristeva, 1980

We live for most of our lives between the extremities of infancy and death. Exposure to either of these states is often felt with apprehension, anxiety or terror — whether the warm and pulsatile womb or the cold recalcitrant corpse, in their company we are made profoundly aware that the borderlines which covet subjecthood are provisional and easily punctured. Rules, and therefore taboos, about what constitute the human body have long been established to obviate the wretchedness of our inevitable death, or the psychological estrangement one may continue to feel toward their childhood. Illness, trauma and disassociation are but some of the proximate conditions that destabilise our rational sense of self — erupting through the liminal space between life and death. Through desublimation and transgression, one may surrender to these horrors of indeterminacy at the exact moment of embracing their visceral power.

Standing in front of the amorphous and devouring bodies that populate the work of Elsa Rouy, without question we are brought closer to this contradictory impulse. Writing in her seminal work of feminist psychoanalysis, The Powers of Horror, Julia Kristeva gave name to this formative and ambiguous tormentor: “The abject. It is something rejected from which one does not part, from which one does not protect oneself as from an object. Imaginary uncanniness and real threat, it beckons to us and ends up engulfing us.” Exemplified in the undulating currents of spittle, menstrual blood and sexual discharge that flow between Rouy’s weightless figures, the abject is that which troubles subjecthood, disrupting categories of self and other — it is a phantasmic substance not only alien to the subject but intimate with it.

These bodily fluids, not only are they horrific through their association with the maternal body made strange, even repulsive, through repression, but “this defilement, this shit is what life withstands, hardly and with difficulty, on the part of death.” The climax of abjection, for Kristeva, is moreover when the prospect of death intersects directly with its antithesis: the innocence and vitality of childhood. Displayed in a deliberate and rhythmic sequence, Rouy’s androgynous and infantile protagonist writhes between these two transformative states. They are at once the suckling newborn — bound to its surroundings by an inverted umbilical cord of physical penetration and gushing amniotic fluids — as they are the threatening presence of contagion, disease and addiction. The room itself is suffuse with scents of Geranium, Ylang Ylang, Jasmine and Neroli, at once subtle and beautiful as they are a visceral metaphor for viral transmission and mortality.

The image of arrested childhood is repeated throughout A Demon in a Sundress, first as bald and glossy textures of skin that stretch and contort across canvas, and second as a series of latex sculptures collapsed lifelessly on the ground — an image of the body turned inside out, of the subject literally abjected, thrown out. Rouy’s figures point to the gap that exists between our imagined and actual body-images, against fascist regimes of the perfect body and the reality of misrecognition that we attempt to fill with entertainment images and fashion models every day and every night of our lives. In either case, it is certainly true that Rouy’s work engages with and excites the politics of the gaze. To be sure, the masculine perspective is subverted. However, it is the feeling that the gaze itself has been problematised, made obscene or obliterated, that is paramount; as if the abject were weaponised or given agency over us, looking back at us through the work. In the words of Hal Foster, the abject reveals itself here “as if there were no scene to stage it, no frame of representation to contain it, no screen.”

What I find most enrapturing about Rouy’s work is not only this impulse to erode the subject in service of the real, but the simultaneity in which this symbolic rupture is coupled with a desire for love, catharsis and co-dependency. Despite a tacit voyeurism that remains in our fascination with monstrosity and deviance, it is the complexity and intensity of our own everyday relationships that come to define A Demon in a Sundress. We see how love can twist into jealously, desire sharpen into lust, and dependency slide into addiction. This redemption of affect produces a nuanced and vulnerable subject, exposed to the traumatic dimension of the abject whilst striving for a language that can nevertheless act as a testimonial against this oppression. A Demon in a Sundress is one such testimonial. It is a softly malevolent reminder that the human is not quite the transcendent position we often believe it to be. “On the edge of non-existence and hallucination; of a reality that — if I acknowledge it — annihilates me”, Kristeva writes, “There, abject and abjection are my safeguards.”

Charlie Mills