CORBIN SHAW: NOWT AS QUEER AS FOLK

Solo exhibition by Corbin Shaw and the inaugural opening of Guts Gallery’s new HQ in London.

Corbin Shaw

‘Nowt As Queer As Folk’

10 Feb - 3 March 2022

Guts Gallery

Unit 2 Sidings House, 10 Andre Street, Hackney E8 2AA

Opening: 10 Feb 6-9pm

Regular Hours: Tues-Sat 10-6pm

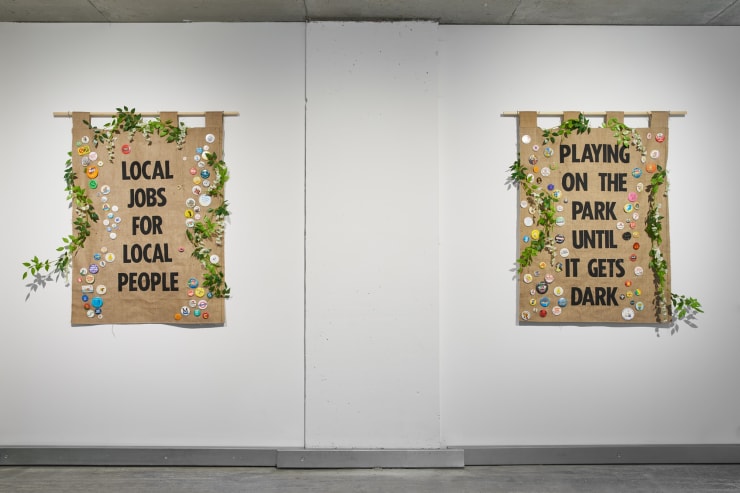

‘Nowt As Queer As Folk’ is a solo exhibition by Corbin Shaw and the inaugural opening of Guts Gallery’s new HQ in London.

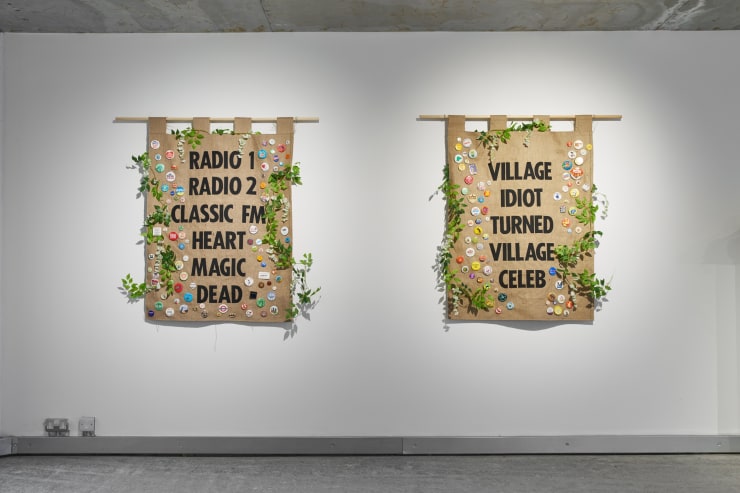

In this exhibition, Shaw explores the enchanted, the political, the ordinary and the often mythical traditions of English village life. Using iconographies and cultural elements of folk to comment on the state of Northern villages in 2022.

Folklore and folk music have long upheld a set of customs and traditions as a way of life for many communities in rural Britain. For hundreds of years phrases and songs often rooted in the past, have passed through generations as a form of oral communication and storytelling that has kept the spirit of folk alive.

Folk is widely left open to interpretation, unrecorded past a certain point in history; its beliefs, practises and customs have been politicised, stolen and embedded with hearsay adapting to individuals own take on the culture.

Outlined in Adam Curtis’ 2021 documentary, ‘Can’t Get You Out of My Head’, the history of folk was hijacked by musicians like Cecil Sharp, who used British folk songs as a tool to bolster British pride and hide the true issues or political agendas that were at large in the country at that time. Responsible for popularising folk music in Britain, Sharp’s releases were a tool to promote his right wing, racist and sexist ideals that tried to shape a new identity for the country through oral communication, that excluded any non-British identities or origins.

Folk or the illusion of folk had the ability to cover up and ignore real issues that rippled through Britain by creating a falsehood of safety for those residing in those areas.

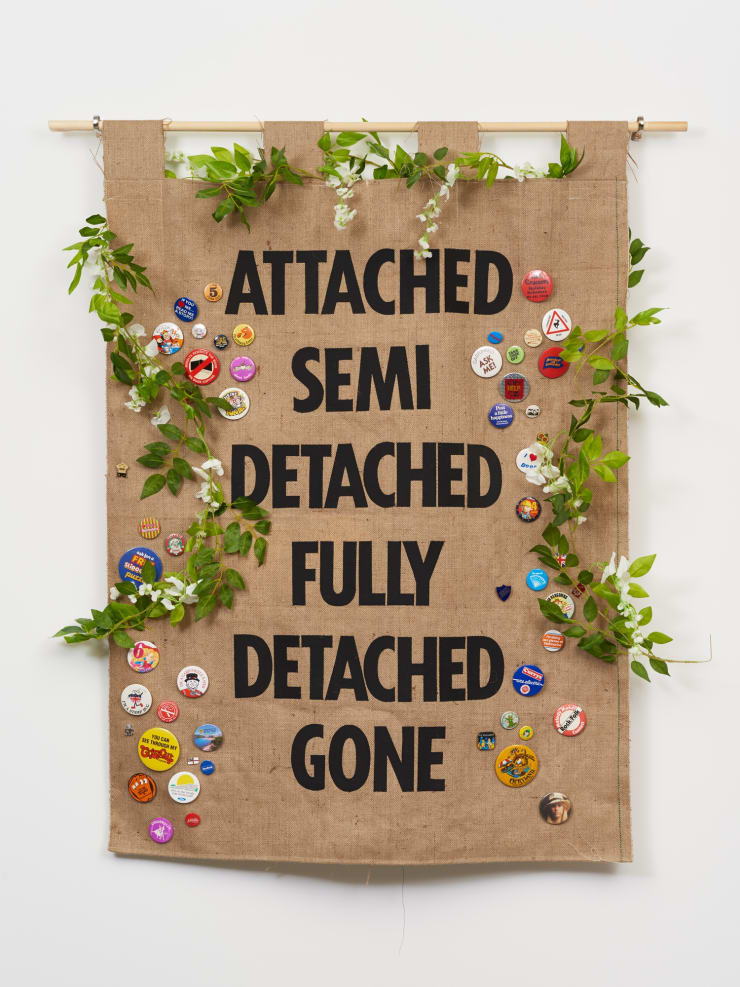

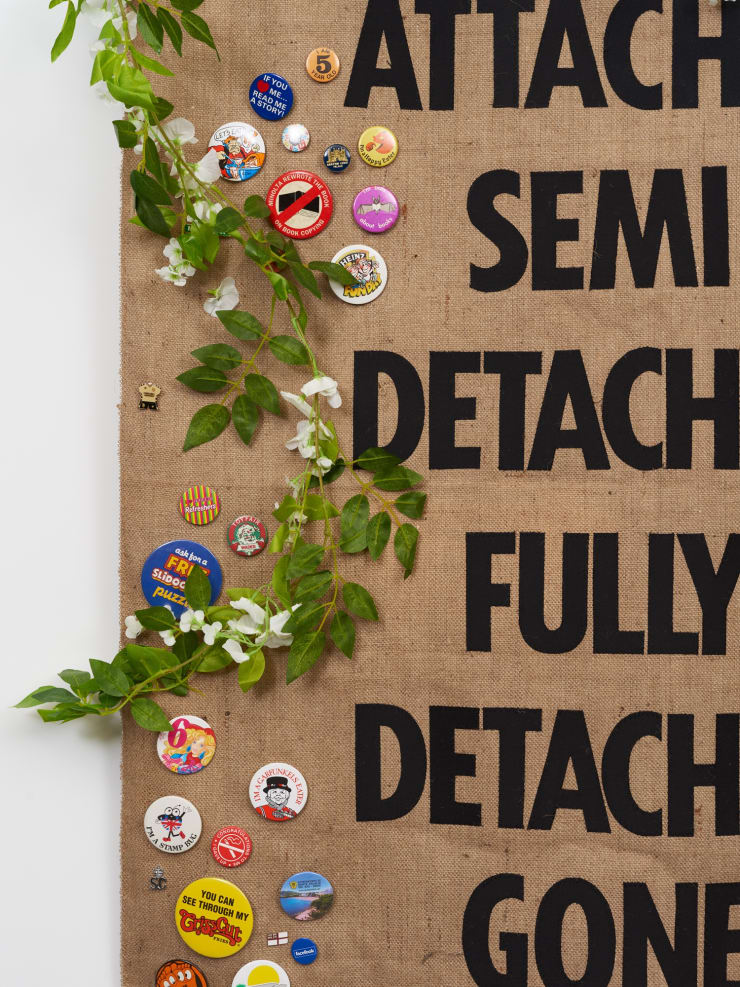

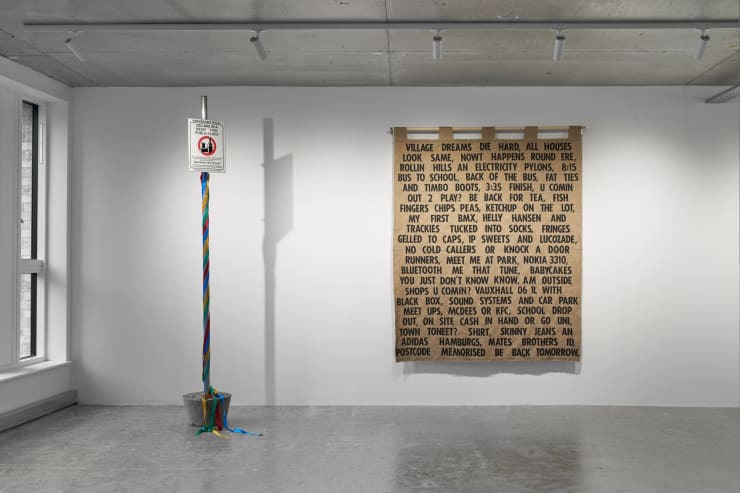

Situated around Shaw’s years spent living in his hometown of Harthill, South Yorkshire, the works in the exhibition centre around a well. Well dressing, also known as ‘well flowering’ is a tradition practised in specifically the Derbyshire and South Yorkshire area in which water sources such as wells are embellished and adorned with flower petals. Speculated to have begun as a pagan custom of offering thanks to the Gods for a consistent water supply; other literature suggests it formed as a celebration for the purity of water after villages survived the Black Death. Although its origins are obscure the tradition is still to this day practised across the villages and towns of Derbyshire and South Yorkshire.

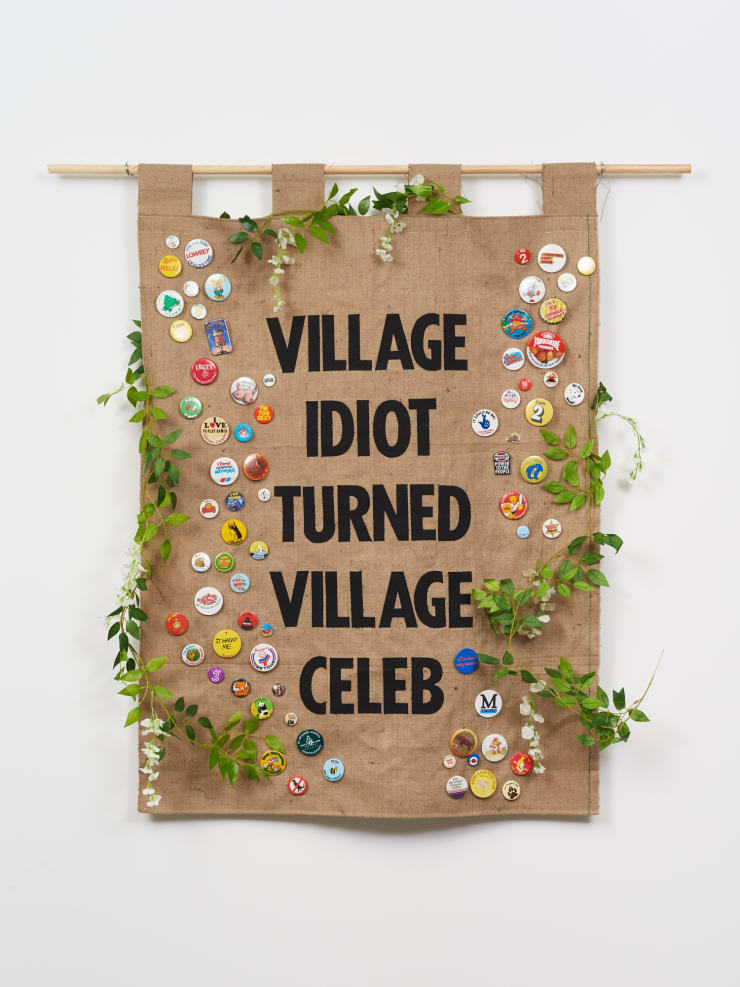

Shaw reimagines the well as a shrine, talking about both the history and the modern-day Harthill, commemorating the characters that live in the village, the everyday people and their lives.

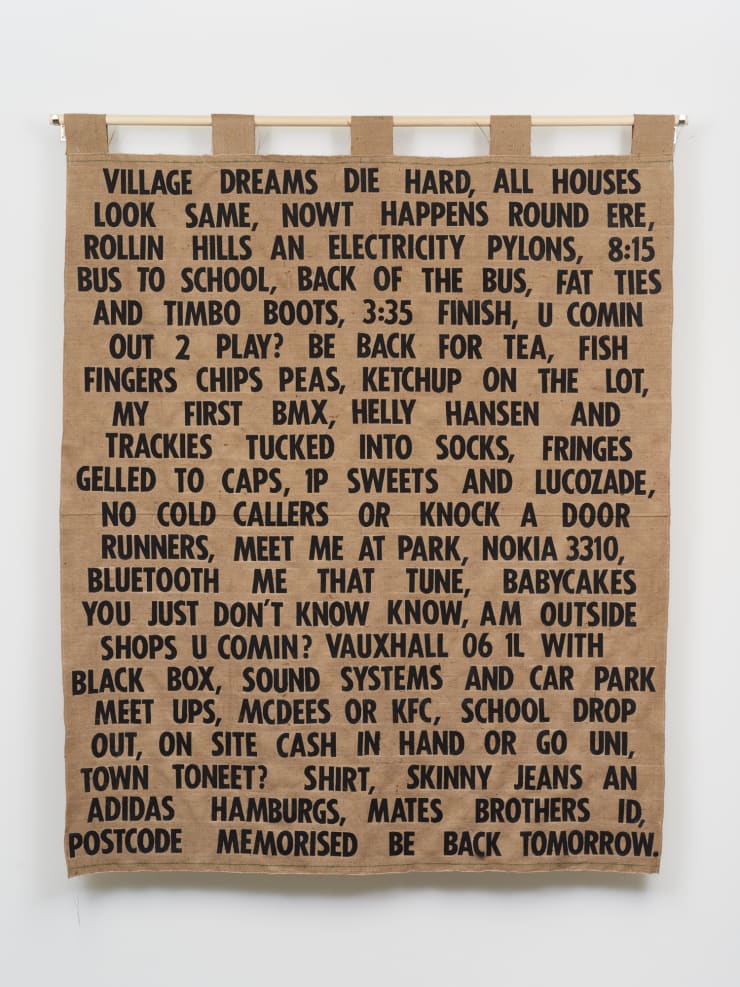

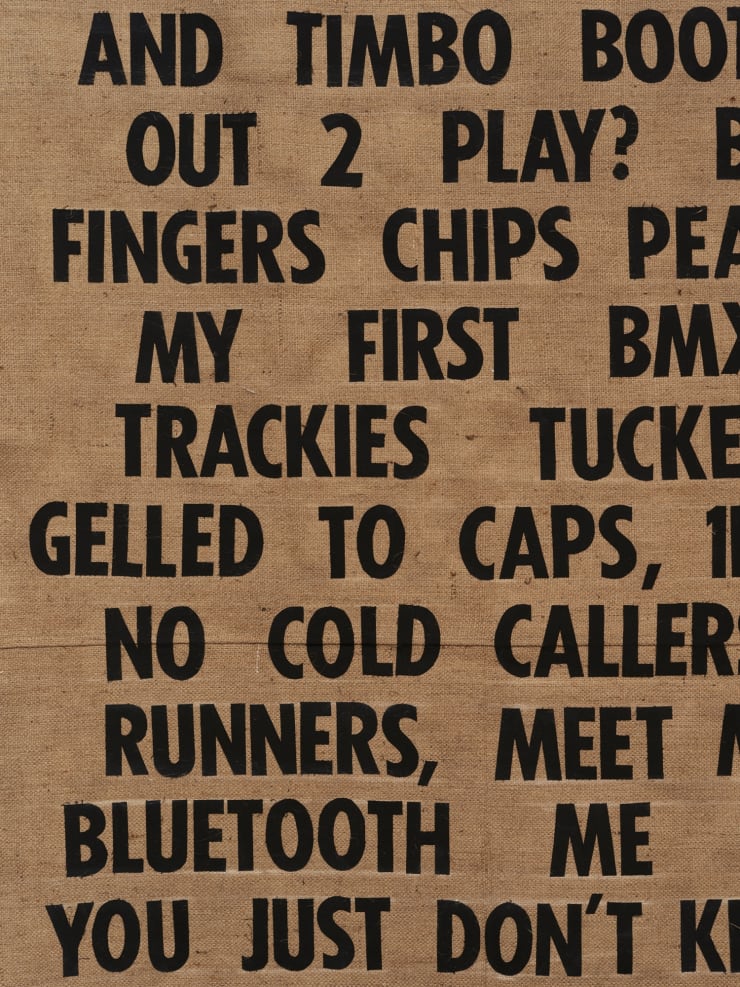

Modern-day village life has become a far cry from the idolised, picturesque folkish depictions. Its green rolling hills, historic towns and rich culture is not a reality that is representative of everyday English people and how they live. Young people in rural communities are often marginalised, with fewer opportunities for jobs, public transport and poor education. Village life is a far cry from how people from cities imagine it to be.

Shaw has chosen to emphasise this lost enchantment with village life through weaving and stitching phrases and slang from contemporary village culture onto tapestries, banners and on the well as emblems and a passage from old village life to the modern here and now. Enlightening us to the suspicions and safety of contemporary village life.

Unlike Sharp, Shaw’s ode to Harthill and its well dressing tradition revokes a hijacking of folk that emulates that of the Leftist folk revivalists such as Ewen MacColl. MacColl aired folk ballads that brought art and ideology together that honoured the working class, commemorating the everyday people and their trades.

History offers depictions of a country melancholic about the loss of its Empire, power hungry and secretive about its true agendas hiding behind flowers and folk dance. We witnessed in our current climate the roots of Brexit that hold onto that mythical, nostalgic idea of England that was invented in those years.

‘Nowt As Queer As Folk’ is both an exhibition and a social commentary on the livelihood of these rural communities, their cultures and the power they can have to sway perceptions, votes, ideologies for the better and the worse.

“In Britain at the start of the 20th century, not only were those in charge frightened by what they’d done abroad with the slave trade and in China but they now had a feeling it was coming closer, that something dangerous might also be happening inside England itself.

The empire had led to giant industrial cities rising up and across England. They were dark, frightening places where millions of people lived in appalling conditions. What alarmed those in charge was the violence and anger that was building up there among what was called the masses. But the danger also seemed to come from the top of society as well. From the new industrialists and bankers who ran the global empire, they also seemed to be out of control. There was a wave of financial scandals and no one seemed to be able to stop them. The novelist E.M Forster wrote, “England is being menaced by the inner darkness in high places that has come with this industrial age”.

Trapped by what they saw as a danger below and corruption above, the middle classes retreated, they turned away into another imaginary version of England where there were none of these threats. It was invented for them by a whole generation of writers, artists and musicians. In an act of collective imagination, they created a complete dream image of England's past - one that still haunts the country today. At its heart was a vision of a natural order in the countryside outside the cities. One of the key figures was a man called Cecil Sharp, he travelled through England recording old songs, and he filmed himself and his friends learning old rural dances.

Sharp made it absolutely clear that this was a political project, his aim was to create a new kind of English nationalism which at its heart had the idea of the ‘Folk’. It was a concept that he had taken from German nationalism, the innocent rural people and their culture. What was implicit in Sharpe’s vision was an England before mass democracy had come. An England where villages lived in harmony and safety taken care of by the lord of the manor.

Sharp was not alone, in 1914 a festival was started in Glastonbury, it ran every year until 1927. It was organised by Rutland Bowten who wanted it to be the centre of this English culture. He composed an opera festival which became a national sensation, it was called ‘the immortal hour’. It is set in a dark mysterious wood where there are powerful and ancient forces. They can be frightening but they are also a way of connecting with a natural order of power in England, they are the lordly ones.”

- Extract from Adam Curtis ‘Can’t Get You Out of My Head’ Series 1:5 Part Five - The Lordly Ones

Corbin Shaw is a multidisciplinary artist who works mainly with video, sound and sculpture. Shaw’s practice explores the performance of masculinity in heteronormative spaces dominated by men. He examines how public notions of masculinity are shaped and how young men conform and disrupt traditional standards of masculinity. Shaw is interested in examining the enforcement of gender roles by the father figure and how those roles have developed through the rise and fall of industrial Britain. His practice tries to understand the invisible authority of our peers that tells us we should be conforming to strict rules on what our gender should or should not be. He wants to understand how gender norms become established, how they are policed, and how best to disrupt and overcome them.